American Philosophy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the

Retrieved on May 24, 2009 The philosophy of the

Jonathan Edwards was "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as " Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the

Jonathan Edwards was "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as " Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the

edits to a draft version

are in his hand in the

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil and

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil and

Retrieved on July 30, 2008

Pragmatism, which began in the 19th century in America, by the beginning of the 20th century began to be accompanied by other philosophical schools of thought, and was eventually eclipsed by them, though only temporarily. The 20th century saw the emergence of process philosophy, itself influenced by the scientific world-view and

Pragmatism, which began in the 19th century in America, by the beginning of the 20th century began to be accompanied by other philosophical schools of thought, and was eventually eclipsed by them, though only temporarily. The 20th century saw the emergence of process philosophy, itself influenced by the scientific world-view and

The middle of the 20th century was the beginning of the dominance of

The middle of the 20th century was the beginning of the dominance of

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as second-wave feminism, is notable for its impact in philosophy.

The popular mind was taken with Betty Friedan's ''The Feminine Mystique''. This was accompanied by other feminist philosophers, such as Alicia Ostriker and Adrienne Rich. These philosophers critiqued basic assumptions and values like objectivity and what they believe to be masculine approaches to ethics, such as rights-based political theories. They maintained there is no such thing as a value-neutral inquiry and they sought to analyze the social dimensions of philosophical issues.

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as second-wave feminism, is notable for its impact in philosophy.

The popular mind was taken with Betty Friedan's ''The Feminine Mystique''. This was accompanied by other feminist philosophers, such as Alicia Ostriker and Adrienne Rich. These philosophers critiqued basic assumptions and values like objectivity and what they believe to be masculine approaches to ethics, such as rights-based political theories. They maintained there is no such thing as a value-neutral inquiry and they sought to analyze the social dimensions of philosophical issues.

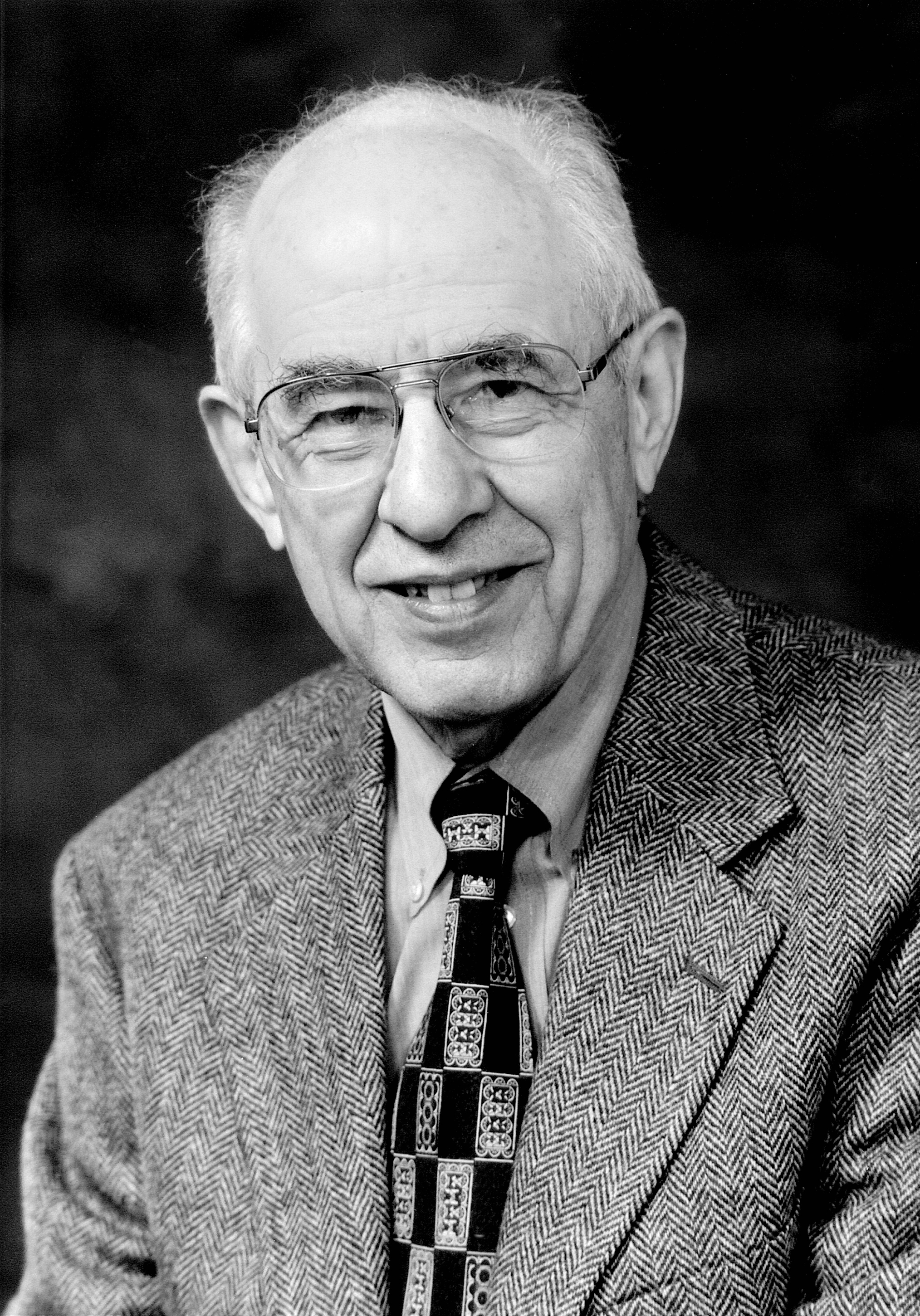

Towards the end of the 20th century there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are Hilary Putnam and Richard Rorty. Rorty is famous as the author of ''Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'' and ''Philosophy and Social Hope''. Hilary Putnam is well known for his quasi-empiricism in mathematics, his challenge of the brain in a vat thought experiment, and his other work in philosophy of mind,

Towards the end of the 20th century there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are Hilary Putnam and Richard Rorty. Rorty is famous as the author of ''Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'' and ''Philosophy and Social Hope''. Hilary Putnam is well known for his quasi-empiricism in mathematics, his challenge of the brain in a vat thought experiment, and his other work in philosophy of mind,

American Philosophical Association

American Philosophical Society

Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy

{{United States topics American philosophy, American literature American culture History of the United States

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''IEP'') is a scholarly online encyclopedia, dealing with philosophy, philosophical topics, and philosophers. The IEP combines open access publication with peer reviewed publication of original pape ...

'' notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can nevertheless be seen as both reflecting and shaping collective American identity over the history of the nation"."American philosophy" at the Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyRetrieved on May 24, 2009 The philosophy of the

founders of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the war for independence from Great Britai ...

is largely seen as an extension of the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. A small number of philosophies are known as American in origin, namely pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

and transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

, with their most prominent proponents being the philosophers William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

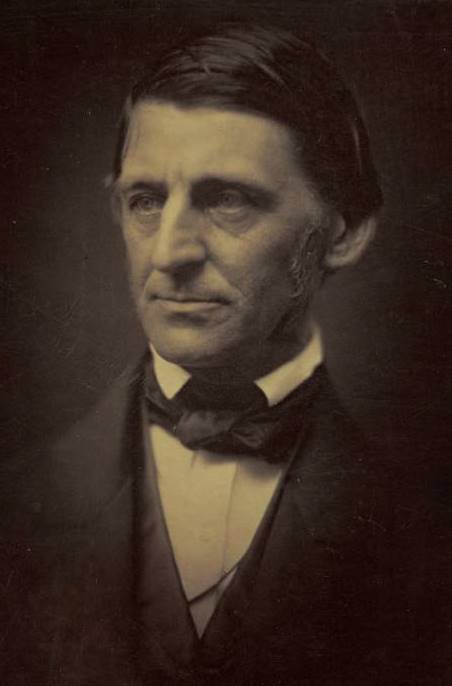

and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

respectively.

17th century

The American philosophical tradition began with the arrival of well-educatedPuritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. They set the earliest American philosophy into the religious tradition (Puritan Providentialism

In Christianity, providentialism is the belief that all events on Earth are controlled by God.

Belief

Providentialism was sometimes viewed by its adherents as differing between national providence and personal providence. Some English and Americ ...

), and there was also an emphasis on the relationship between the individual and the community. This is evident by the early colonial documents such as the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

The Fundamental Orders were adopted by the Connecticut Colony council on . The fundamental orders describe the government set up by the Connecticut River towns, setting its structure and powers. They wanted the government to have access to the ...

(1639) and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was the first legal code established in New England, compiled by Puritan minister Nathaniel Ward. The laws were established by the Massachusetts General Court in 1641. The Body of Liberties begins by establishin ...

(1641).

Thinkers such as John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

emphasized the public life over the private. Holding that the former takes precedence over the latter, while other writers, such as Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

(co-founder of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

) held that religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

was more integral than trying to achieve religious homogeneity in a community.

18th century

18th-century American philosophy may be broken into two halves, the first half being marked by the theology of ReformedPuritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

influenced by the Great Awakening as well as Enlightenment natural philosophy, and the second by the native moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

of the American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution, and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was ...

taught in American colleges. They were used "in the tumultuous years of the 1750s and 1770s" to "forge a new intellectual culture for the United states", which led to the American incarnation of the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

that is associated with the political thought

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

of the Founding Fathers.

The 18th century saw the introduction of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

and the Enlightenment philosophers Descartes, Newton, Locke, Wollaston, and Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

to Colonial British America. Two native-born Americans, Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

and Jonathan Edwards, were first influenced by these philosophers; they then adapted and extended their Enlightenment ideas to develop their own American theology and philosophy. Both were originally ordained Puritan Congregationalist ministers who embraced much of the new learning of the Enlightenment. Both were Yale educated and Berkeley influenced idealists

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely con ...

who became influential college presidents. Both were influential in the development of American political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

and the works of the Founding Fathers. But Edwards based his reformed Puritan theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

on Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

doctrine, while Johnson converted to the Anglican episcopal religion (the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

), then based his new American moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

on William Wollaston's Natural Religion

Natural religion most frequently means the "religion of nature", in which God, the soul, spirits, and all objects of the supernatural are considered as part of nature and not separate from it. Conversely, it is also used in philosophy to describe s ...

. Late in the century, Scottish innate or common sense realism replaced the native schools of these two rivals in the college philosophy curricula of American colleges; it would remain the dominant philosophy in American academia up to the Civil War.

Introduction of the Enlightenment into America

The first 100 years or so of college education in the American Colonies were dominated in New England by the Puritan theology ofWilliam Ames

William Ames (; Latin: ''Guilielmus Amesius''; 157614 November 1633) was an English Puritan minister, philosopher, and controversialist. He spent much time in the Netherlands, and is noted for his involvement in the controversy between the Cal ...

and "the sixteenth-century logical methods of Petrus Ramus

Petrus Ramus (french: Pierre de La Ramée; Anglicized as Peter Ramus ; 1515 – 26 August 1572) was a French humanist, logician, and educational reformer. A Protestant convert, he was a victim of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Early life

...

." Then in 1714, a donation of 800 books from England, collected by Colonial Agent A colonial agent was the official representative of a British colony based in London during the British Empire. About 200 men served. They were selected and paid a fixed salary by the colonial government, and given the long delays in communication ...

Jeremiah Dummer

Jeremiah Dummer (1681 – May 19, 1739) was an important colonial figure for New England in the early 18th century. His most significant contributions to American history were his ''A Defense of the New England Charters'' and his role in the for ...

, arrived at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

.Ellis, Joseph J., ''The New England Mind in Transition: Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, 1696–1772,'' Yale University Press, 1973, p. 34 They contained what became known as "The New Learning", including "the works of Locke, Descartes, Newton, Boyle

Boyle is an English, Irish and Scottish surname of Gaelic, Anglo-Saxon or Norman origin. In the northwest of Ireland it is one of the most common family names. Notable people with the surname include:

Disambiguation

*Adam Boyle (disambiguation), ...

, and Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

", and other Enlightenment era

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

authors not known to the tutors and graduates of Puritan Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

and Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

colleges. They were first opened and studied by an eighteen-year-old graduate student from Guilford, Connecticut

Guilford is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut, United States, that borders Madison, Branford, North Branford and Durham, and is situated on I-95 and the Connecticut seacoast. The population was 22,073 at the 2020 census.

History

Guilfo ...

, the young American Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

, who had also just found and read Lord Francis Bacon's '' Advancement of Learning.'' Johnson wrote in his ''Autobiography'', "All this was like a flood of day to his low state of mind" and that "he found himself like one at once emerging out of the glimmer of twilight into the full sunshine of open day." He now considered what he had learned at Yale "nothing but the scholastic cobwebs of a few little English and Dutch systems that would hardly now be taken up in the street."

Johnson was appointed tutor at Yale in 1716. He began to teach the Enlightenment curriculum there, and thus began the American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution, and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was ...

. One of his students for a brief time was a fifteen-year-old Jonathan Edwards. "These two brilliant Yale students of those years, each of whom was to become a noted thinker and college president, exposed the fundamental nature of the problem" of the "incongruities between the old learning and the new." But each had a quite different view on the issues of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

versus freewill, original sin versus the pursuit of happiness though practicing virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

, and the education of children.

Reformed Calvinism

Jonathan Edwards was "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as " Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the

Jonathan Edwards was "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as " Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

), Edwards emphasized "the absolute sovereignty of God and the beauty of God's holiness." Working to unite Christian Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at le ...

with an empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

, with the aid of Newtonian physics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classical mec ...

, Edwards was deeply influenced by George Berkeley, himself an empiricist, and Edwards derived his importance of the immaterial for the creation of human experience from Bishop Berkeley.

The non-material mind consists of understanding and will, and it is understanding, interpreted in a Newtonian framework, that leads to Edwards' fundamental metaphysical category of Resistance. Whatever features an object may have, it has these properties because the object resists. Resistance itself is the exertion of God's power, and it can be seen in Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

, where an object is "unwilling" to change its current state of motion; an object at rest will remain at rest and an object in motion will remain in motion.

Though Edwards reformed Puritan theology using Enlightenment ideas from natural philosophy, and Locke, Newton, and Berkeley, he remained a Calvinist and hard determinist

Hard determinism (or metaphysical determinism) is a view on free will which holds that determinism is true, that it is incompatible with free will, and therefore that free will does not exist. Although hard determinism generally refers to nomol ...

. Jonathan Edwards also rejected the freedom of the will, saying that "we can do as we please, but we cannot please as we please." According to Edwards, neither good works nor self-originating faith lead to salvation, but rather it is the unconditional grace of God which stands as the sole arbiter of human fortune.

Enlightenment

While the 17th- and early 18th-century American philosophical tradition was decidedly marked by religious themes and the Reformation reason of Ramus, the 18th century saw more reliance onscience

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

and the new learning of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, along with an idealist belief in the perfectibility of human beings through teaching ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

and moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

, laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

, and a new focus on political matters.

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

has been called "The Founder of American Philosophy" and the "first important philosopher in colonial America and author of the first philosophy textbook published there". He was interested not only in philosophy and theology, but in theories of education, and in knowledge classification schemes, which he used to write encyclopedias

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

, develop college curricula, and create library classification

A library classification is a system of organization of knowledge by which library resources are arranged and ordered systematically. Library classifications are a notational system that represents the order of topics in the classification and al ...

systems.

Johnson was a proponent of the view that "the essence of true religion is morality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of cond ...

", and believed that "the problem of denominationalism

A religious denomination is a subgroup within a religion that operates under a common name and tradition among other activities.

The term refers to the various Christian denominations (for example, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic, and the many variet ...

" could be solved by teaching a non-denominational common moral philosophy acceptable to all religions. So he crafted one. Johnson's moral philosophy was influenced by Descartes and Locke, but more directly by William Wollaston

William Wollaston (; 26 March 165929 October 1724) was a school teacher, Church of England priest, scholar of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, theologian, and a major Enlightenment era English philosopher. He is remembered today for one book, which he ...

's '' Religion of Nature Delineated'' and the idealist philosopher of George Berkeley, with whom Johnson studied while Berkeley was in Rhode Island between 1729 and 1731. Johnson strongly rejected Calvin's doctrine of Predestination and believed that people were autonomous moral agents endowed with freewill and Lockean natural rights. His fusion philosophy of Natural Religion and Idealism, which has been called "American Practical Idealism", was developed as a series of college textbooks in seven editions between 1731 and 1754. These works, and his dialogue ''Raphael, or The Genius of the English America, ''written at the time of the Stamp Act crisis, go beyond his Wollaston and Berkeley influences; ''Raphael ''includes sections on economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

, the teaching of children, and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

.

His moral philosophy is defined in his college textbook ''Elementa Philosophica'' as "the Art of pursuing our highest Happiness by the practice of virtue". It was promoted by President Thomas Clap

Thomas Clap or Thomas Clapp (June 26, 1703 – January 7, 1767) was an American academic and educator, a Congregational minister, and college administrator. He was both the fifth rector and the earliest official to be called "president" of Yale Co ...

of Yale, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

and Provost William Smith at The Academy and College of Philadelphia

The Academy and College of Philadelphia (1749-1791) was a boys' school and men's college in Philadelphia, Colony of Pennsylvania.

Founded in 1749 by a group of local notables that included Benjamin Franklin, the Academy of Philadelphia began as a ...

, and taught at King's College (now Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

), which Johnson founded in 1754. It was influential in its day: it has been estimated that about half of American college students between 1743 and 1776, and over half of the men who contributed to the ''Declaration of Independence'' or debated it were connected to Johnson's American Practical Idealism moral philosophy. Three members of the Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Thi ...

who edited the ''Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

'' were closely connected to Johnson: his educational partner, promoter, friend, and publisher Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, his King's College student Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

of New York, and his son William Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father and statesman. Before the Revolutionary War, he served as a militia lieutenant before being relieved following his rejection of his election to the Fi ...

's legal protegee and Yale treasurer Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Cont ...

of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

. Johnson's son William Samuel Johnson was the Chairman of the Committee of Style that wrote the U.S. Constitutionedits to a draft version

are in his hand in the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

.

Founders' political philosophy

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil and

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

. Many of the Founding Fathers wrote extensively on political issues, including John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

, Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

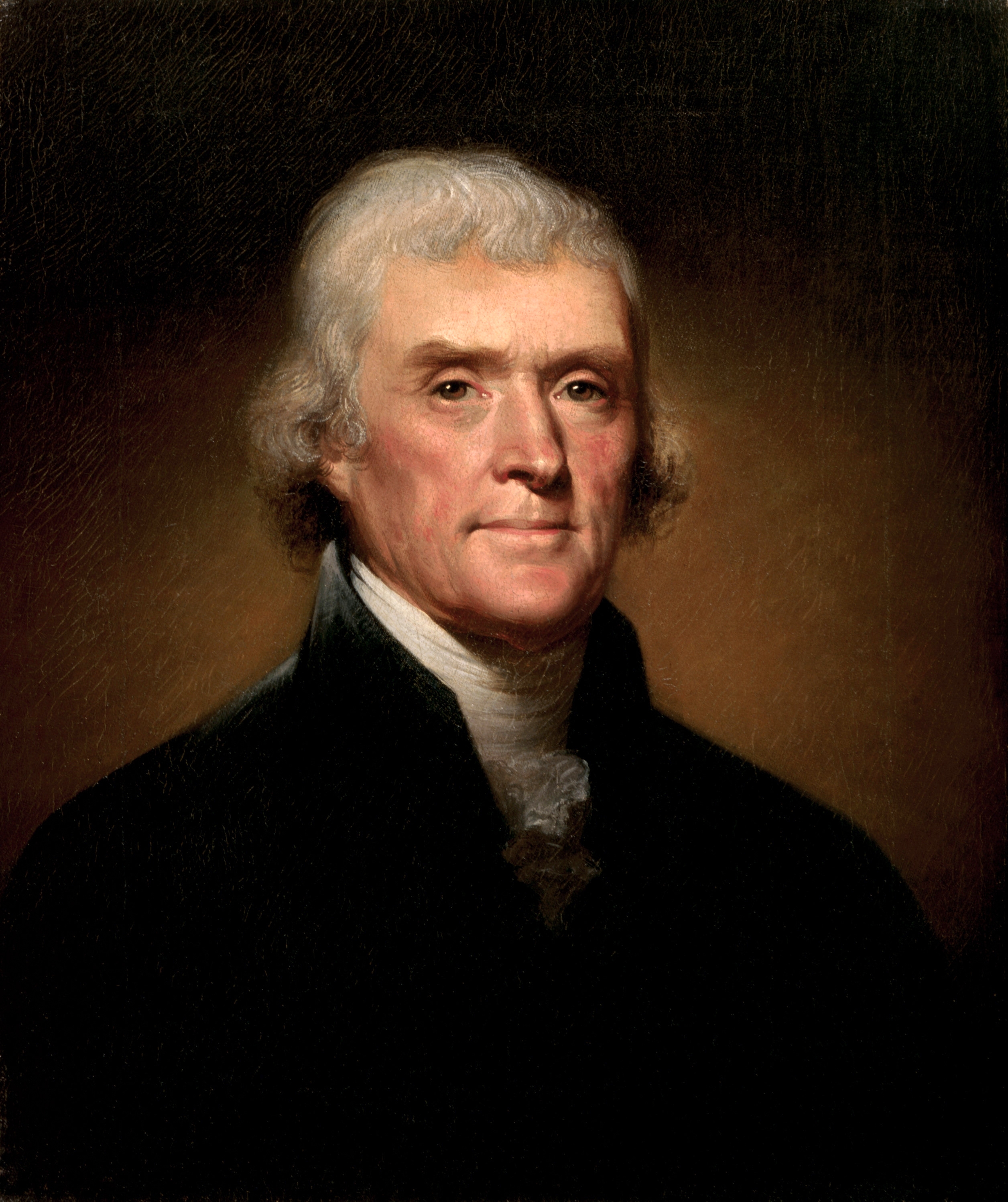

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

. In continuing with the chief concerns of the Puritans in the 17th century, the Founding Fathers debated the interrelationship between God, the state, and the individual. Resulting from this were the ''United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

'', passed in 1776, and the ''United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

'', ratified in 1788.

The Constitution sets forth a federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

and republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

an form of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

that is marked by a balance of powers accompanied by a checks and balances

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

system between the three branches of government: a judicial branch

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, an executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a State (polity), state.

In poli ...

led by the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

, and a legislative branch

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known as ...

composed of a bicameral legislature where the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

is the lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

and the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

is the upper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

.

Although the ''Declaration of Independence'' does contain references to the Creator, the God of Nature, Divine Providence, and the Supreme Judge of the World, the Founding Fathers were not exclusively theistic

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred t ...

. Some professed personal concepts of deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the Philosophy, philosophical position and Rationalism, rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that Empirical evi ...

, as was characteristic of other European Enlightenment thinkers, such as Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

, François-Marie Arouet

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

(better known by his pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

), and Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

. However, an investigation of 106 contributors to the ''Declaration of Independence'' between September 5, 1774, and July 4, 1776, found that only two men (Franklin and Jefferson), both American Practical Idealists in their moral philosophy, might be called quasi-deists or non-denominational Christians; all the others were publicly members of denominational Christian churches. Even Franklin professed the need for a "public religion" and would attend various churches from time to time. Jefferson was vestryman at the evangelical Calvinistical Reformed Church of Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Ch ...

, a church he himself founded and named in 1777, suggesting that at this time of life he was rather strongly affiliated with a denomination and that the influence of Whitefield and Edwards reached even into Virginia. But the founders who studied or embraced Johnson, Franklin, and Smith's non-denominational moral philosophy were at least influenced by the deistic tendencies of Wollaston's Natural Religion, as evidenced by "the Laws of Nature, and Nature's God" and "the pursuit of Happiness" in the ''Declaration''.

An alternate moral philosophy to the domestic American Practical Idealism, called variously Scottish Innate Sense moral philosophy (by Jefferson), Scottish Commonsense Philosophy, or Scottish common sense realism, was introduced into American Colleges in 1768 by John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense real ...

, a Scottish immigrant and educator who was invited to be President of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

). He was a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

minister and a delegate who joined the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

just days before the ''Declaration'' was debated. His moral philosophy was based on the work of the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson, who also influenced John Adams. When President Witherspoon arrived at the College of New Jersey in 1768, he expanded its natural philosophy offerings, purged the Berkeley adherents from the faculty, including Jonathan Edwards Jr., and taught his own Hutcheson-influenced form of Scottish innate sense moral philosophy. Some revisionist commentators, including Garry Wills' ''Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence'', claimed in the 1970s that this imported Scottish philosophy was the basis for the founding documents of America. However, other historians have questioned this assertion. Ronald Hamowy published a critique of Garry Wills's ''Inventing America'', concluding that "the moment ills'sstatements are subjected to scrutiny, they appear a mass of confusions, uneducated guesses, and blatant errors of fact." Another investigation of all of the contributors to the ''United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

'' suggests that only Jonathan Witherspoon and John Adams embraced the imported Scottish morality. While Scottish innate sense realism would in the decades after the Revolution become the dominate moral philosophy in classrooms of American academia for almost 100 years, it was not a strong influence at the time of the ''Declaration'' was crafted. Johnson's American Practical Idealism and Edwards' Reform Puritan Calvinism were far stronger influences on the men of the Continental Congress and on the ''Declaration''.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

, the English intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

, pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articulate a poli ...

, and revolutionary who wrote ''Common Sense'' and ''Rights of Man

''Rights of Man'' (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the ...

'' was an influential promoter of Enlightenment political ideas in America, though he was not a philosopher. ''Common Sense'', which has been described as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era", provides justification for the American revolution and independence from the British Crown. Though popular in 1776, historian Pauline Maier

Pauline Alice Maier (née Rubbelke; April 27, 1938 – August 12, 2013) was a revisionist historian of the American Revolution, whose work also addressed the late colonial period and the history of the United States after the end of the Revolut ...

cautions that, "Paine's influence was more modest than he claimed and than his more enthusiastic admirers assume."

In summary, "in the middle eighteenth century," it was "the collegians who studied" the ideas of the new learning and moral philosophy taught in the Colonial colleges who "created new documents of American nationhood." It was the generation of "Founding Grandfathers", men such as President Samuel Johnson, President Jonathan Edwards, President Thomas Clap, Benjamin Franklin, and Provost William Smith, who "first created the idealistic moral philosophy of 'the pursuit of Happiness', and then taught it in American colleges to the generation of men who would become the Founding Fathers."

19th century

The 19th century saw the rise ofRomanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

in America. The American incarnation of Romanticism was transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

and it stands as a major American innovation. The 19th century also saw the rise of the school of pragmatism, along with a smaller, Hegelian

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

philosophical movement led by George Holmes Howison

George Holmes Howison (29 November 1834 – 31 December 1916) was an American philosopher who established the philosophy department at the University of California, Berkeley and held the position there of Mills Professor of Intellectual and Moral ...

that was focused in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, though the influence of American pragmatism far outstripped that of the small Hegelian movement.

Other reactions to materialism included the "Objective idealism

Objective idealism is a form of metaphysical idealism that accepts Naïve realism (the view that empirical objects exist objectively) but rejects epiphenomenalist materialism (according to which the mind and spiritual values have emerged due to ...

" of Josiah Royce

Josiah Royce (; November 20, 1855 – September 14, 1916) was an American objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his version of personalism, defense of absolutism, idealism and his ...

, and the "Personalism

Personalism is an intellectual stance that emphasizes the importance of human persons. Personalism exists in many different versions, and this makes it somewhat difficult to define as a philosophical and theological movement. Friedrich Schleierm ...

," sometimes called "Boston personalism," of Borden Parker Bowne

Borden Parker Bowne (January 14, 1847 – April 1, 1910) was an American Christian philosopher, Methodist minister and theologian. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature nine times.

Life

Bowne was born on January 14, 1847, near Leona ...

.

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

and intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, the development, and the exercise of the intellect; and also identifies the life of the mind of the intellectual person. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''inte ...

in general and the mechanistic, reductionistic

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical po ...

worldview in particular. Transcendentalism is marked by the holistic

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book ''Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED Onl ...

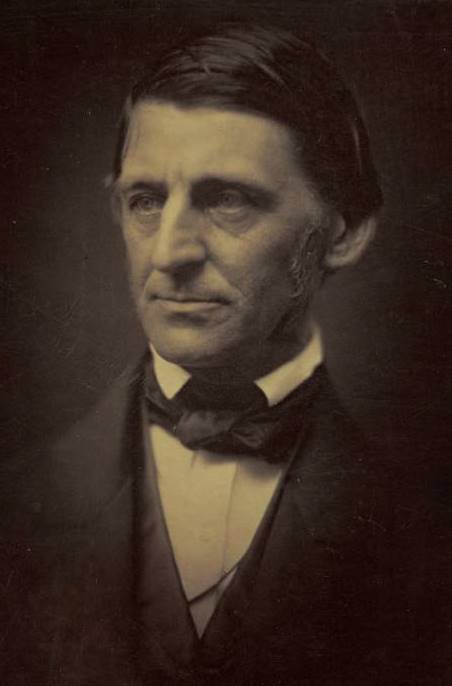

belief in an ideal spiritual state that 'transcends' the physical and empirical, and this perfect state can only be attained by one's own intuition and personal reflection, as opposed to either industrial progress and scientific advancement or the principles and prescriptions of traditional, organized religion. The most notable transcendentalist writers include Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

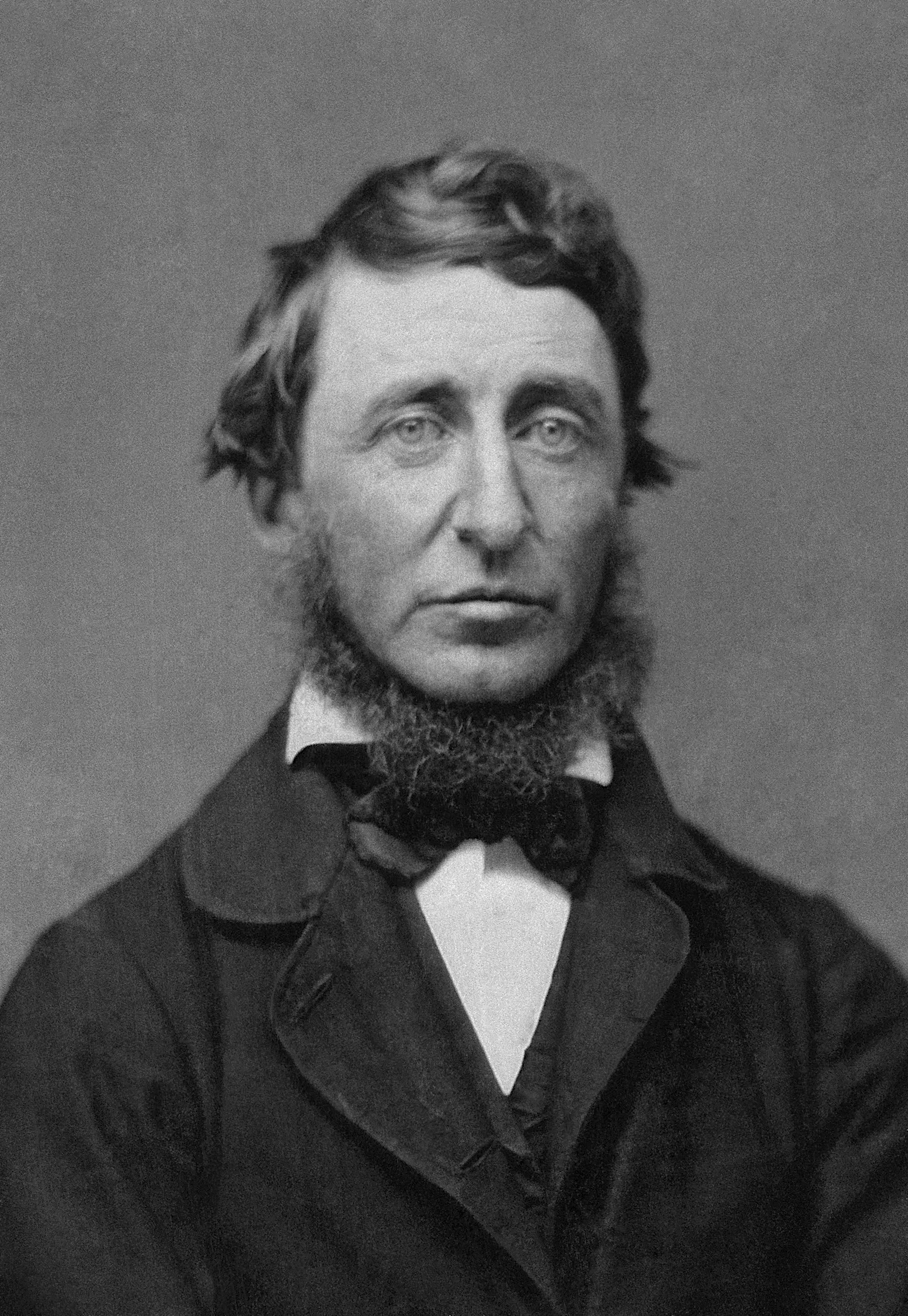

, Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural su ...

, and Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

.

The transcendentalist writers all desired a deep return to nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

, and believed that real, true knowledge is intuitive and personal and arises out of personal immersion and reflection in nature, as opposed to scientific knowledge that is the result of empirical sense experience.

Things such as scientific tools, political institutions, and the conventional rules of morality as dictated by traditional religion need to be transcended. This is found in Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural su ...

's '' Walden; or, Life in the Woods'' where transcendence is achieved through immersion in nature and the distancing of oneself from society.

Darwinism in America

The release ofCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's evolutionary theory

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in his 1859 publication of ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' had a strong impact on American philosophy. John Fiske and Chauncey Wright

Chauncey Wright (September 10, 1830 – September 12, 1875) was an American philosopher and mathematician, who was an influential early defender of Darwinism and an important influence on American pragmatists such as Charles Sanders Peirce and Wi ...

both wrote about and argued for the re-conceiving of philosophy through an evolutionary lens. They both wanted to understand morality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of cond ...

and the mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

in Darwinian terms, setting a precedent for evolutionary psychology

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in psychology that examines cognition and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify human psychological adaptations with regards to the ancestral problems they evolv ...

and evolutionary ethics

Evolutionary ethics is a field of inquiry that explores how evolutionary theory might bear on our understanding of ethics or morality. The range of issues investigated by evolutionary ethics is quite broad. Supporters of evolutionary ethics have ...

.

Darwin's biological theory was also integrated into the social and political philosophies of English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

thinker Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest" ...

and American philosopher William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and be ...

. Herbert Spencer, who coined the oft-misattributed term "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

," believed that societies were in a struggle for survival, and that groups within society are where they are because of some level of fitness. This struggle is beneficial to human kind, as in the long run the weak will be weeded out and only the strong will survive. This position is often referred to as Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

, though it is distinct from the eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

movements with which social darwinism is often associated. The laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

beliefs of Sumner and Spencer do not advocate coercive breeding to achieve a planned outcome.

Sumner, much influenced by Spencer, believed along with the industrialist Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

that the social implication of the fact of the struggle for survival is that laissez-faire capitalism is the natural political-economic system and is the one that will lead to the greatest amount of well-being. William Sumner, in addition to his advocacy of free markets, also espoused anti-imperialism (having been credited with coining the term "ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

"), and advocated for the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

.

Pragmatism

The most influential school of thought that is uniquely American ispragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

. It began in the late nineteenth century in the United States with Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

, William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

, and John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

. Pragmatism begins with the idea that belief is that upon which one is willing to act. It holds that a proposition's meaning is the consequent form of conduct or practice that would be implied by accepting the proposition as true."Pragmatism" at IEPRetrieved on July 30, 2008

Charles Sanders Peirce

Polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, logician

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, mathematician, philosopher, and scientist Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

(1839–1914) coined the term "pragmatism" in the 1870s. He was a member of The Metaphysical Club

The Metaphysical Club was a name attributed by the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, in an unpublished paper over thirty years after its foundation, to a conversational philosophical club that Peirce, the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wend ...

, which was a conversational club of intellectuals that also included Chauncey Wright

Chauncey Wright (September 10, 1830 – September 12, 1875) was an American philosopher and mathematician, who was an influential early defender of Darwinism and an important influence on American pragmatists such as Charles Sanders Peirce and Wi ...

, future Supreme Court Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight Associate Justice of the Supreme ...

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist and legal scholar who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932.Holmes was Acting Chief Justice of the Un ...

, and William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

. In addition to making profound contributions to semiotics

Semiotics (also called semiotic studies) is the systematic study of sign processes ( semiosis) and meaning making. Semiosis is any activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, where a sign is defined as anything that communicates something ...

, logic, and mathematics, Peirce wrote what are considered to be the founding documents of pragmatism, " The Fixation of Belief" (1877) and "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878).

In "The Fixation of Belief" Peirce argues for the superiority of the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific m ...

in settling belief on theoretical questions. In "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" Peirce argued for pragmatism as summed up in that which he later called the pragmatic maxim {{C. S. Peirce articles, abbreviations=no

The pragmatic maxim, also known as the maxim of pragmatism or the maxim of pragmaticism, is a maxim of logic formulated by Charles Sanders Peirce. Serving as a normative recommendation or a regulative princ ...

: "Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object". Peirce emphasized that a conception is general, such that its meaning is not a set of actual, definite effects themselves. Instead the conception of an object is equated to a conception of that object's effects to a general extent of their conceivable implications for informed practice. Those conceivable practical implications are the conception's meaning.

The maxim is intended to help fruitfully clarify confusions caused, for example, by distinctions that make formal but not practical differences. Traditionally one analyzes an idea into parts (his example: a definition of truth as a sign's correspondence to its object). To that needful but confined step, the maxim adds a further and practice-oriented step (his example: a definition of truth as sufficient investigation's destined end).

It is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection Reflection or reflexion may refer to:

Science and technology

* Reflection (physics), a common wave phenomenon

** Specular reflection, reflection from a smooth surface

*** Mirror image, a reflection in a mirror or in water

** Signal reflection, in ...

arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the formation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the use and improvement of verification. Typical of Peirce is his concern with inference to explanatory hypotheses as outside the usual foundational alternative between deductivist rationalism and inductivist empiricism, though he himself was a mathematician of logic and a founder of statistics.

Peirce's philosophy includes a pervasive three-category system, both fallibilism

Originally, fallibilism (from Medieval Latin: ''fallibilis'', "liable to err") is the philosophical principle that propositions can be accepted even though they cannot be conclusively proven or justified,Haack, Susan (1979)"Fallibilism and Nece ...

and anti-skeptical belief that truth is discoverable and immutable, logic as formal semiotic (including semiotic elements and classes of signs

Charles Sanders Peirce began writing on semiotics, which he also called semeiotics, meaning the philosophical study of signs, in the 1860s, around the time that he devised his system of three categories. During the 20th century, the term "semiot ...

, modes of inference, and methods of inquiry along with pragmatism and critical common-sensism), Scholastic realism, theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

, objective idealism

Objective idealism is a form of metaphysical idealism that accepts Naïve realism (the view that empirical objects exist objectively) but rejects epiphenomenalist materialism (according to which the mind and spiritual values have emerged due to ...

, and belief in the reality of continuity of space, time, and law, and in the reality of absolute chance, mechanical necessity, and creative love as principles operative in the cosmos and as modes of its evolution.

William James

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

(1842–1910) was "an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy." He is famous as the author of ''The Varieties of Religious Experience

''The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature'' is a book by Harvard University psychologist and philosopher William James. It comprises his edited Gifford Lectures on natural theology, which were delivered at the University o ...

'', his monumental tome ''The Principles of Psychology

''The Principles of Psychology'' is an 1890 book about psychology by William James, an American philosopher and psychologist who trained to be a physician before going into psychology. There are four methods from James' book: stream of consciousne ...

'', and his lecture "The Will to Believe "The Will to Believe" is a lecture by William James, first published in 1896, which defends, in certain cases, the adoption of a belief without prior evidence of its truth. In particular, James is concerned in this lecture about defending the ratio ...

."

James, along with Peirce, saw pragmatism as embodying familiar attitudes elaborated into a radical new philosophical method of clarifying ideas and thereby resolving dilemmas. In his 1910 '' Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking,'' James paraphrased Peirce's pragmatic maxim as follows:

He then went on to characterize pragmatism as promoting not only a method of clarifying ideas but also as endorsing a particular theory of truth. Peirce rejected this latter move by James, preferring to describe the pragmatic maxim only as a maxim of logic and pragmatism as a methodological stance, explicitly denying that it was a substantive doctrine or theory about anything, truth or otherwise.

James is also known for his radical empiricism

Radical empiricism is a philosophical doctrine put forth by William James. It asserts that experience includes both particulars and relations between those particulars, and that therefore both deserve a place in our explanations. In concrete terms: ...

which holds that relations between objects are as real as the objects themselves. James was also a pluralist in that he believed that there may actually be multiple correct accounts of truth. He rejected the correspondence theory of truth and instead held that truth involves a belief, facts about the world, other background beliefs, and future consequences of those beliefs. Later in his life James would also come to adopt neutral monism

Neutral monism is an umbrella term for a class of metaphysical theories in the philosophy of mind. These theories reject the dichotomy of mind and matter, believing the fundamental nature of reality to be neither mental nor physical; in other words ...

, the view that the ultimate reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, r ...

is of one kind, and is neither mental nor physical

Physical may refer to:

*Physical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, or clinical examination, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a medical condition. It generally co ...

.

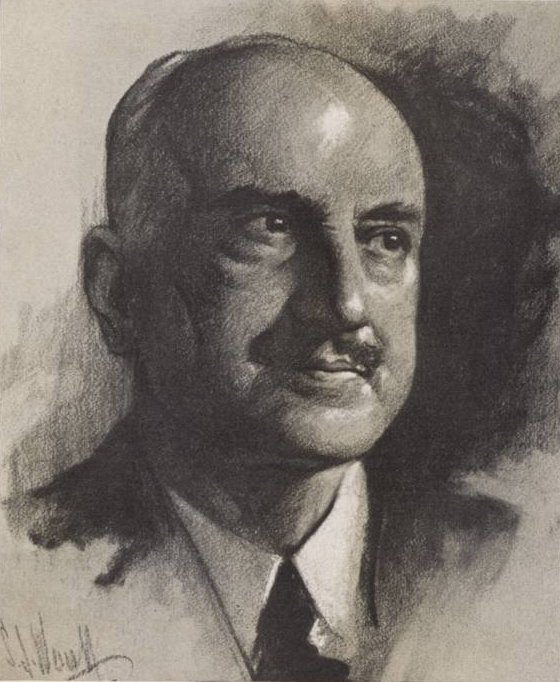

John Dewey

John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

(1859–1952), while still engaging in the lofty academic philosophical work of James and Peirce before him, also wrote extensively on political and social matters, and his presence in the public sphere was much greater than his pragmatist predecessors. In addition to being one of the founding members of pragmatism, John Dewey was one of the founders of functional psychology

Functional psychology or functionalism refers to a psychological school of thought that was a direct outgrowth of Darwinian thinking which focuses attention on the utility and purpose of behavior that has been modified over years of human existen ...

and was a leading figure of the progressive movement in U.S. schooling during the first half of the 20th century.